Glen Keane, the Oscar-profitable artist powering these kinds of Disney classics as The Minimal Mermaid (1989), was once explained by Ed Catmull, the previous president of Pixar and Walt Disney Studios, as “one of the most effective animators in the history of hand-drawn animation.” But when he sat down to design and style Ariel, or without a doubt the beast from Elegance and the Beast (1991), Keane’s thoughts was a blank. He experienced no preconception of what he would draw.

This is due to the fact he has aphantasia, a not long ago recognized variation of human encounter impacting 2% to 5% of the inhabitants, in which a human being is unable to crank out mental imagery. Maybe astonishingly, Keane is not by itself in staying a visible artist who can not visualize.

When aphantasia was named and publicized, a quantity of imaginative practitioners—artists, designers, and architects—contacted the researchers to say that they too had no “mind’s eye.” Intrigued by the seemingly counterintuitive idea, we collected a team of these individuals together and curated an exhibition of their perform.

How is it, then, that a person like Keane can attract a photo of Ariel with out a psychological image to tutorial him?

Recognizing vs. picturing

The initial place to consider is that there is a variance among recognizing or remembering what a thing appears to be like and creating a psychological impression of that thing. To draw it, you only will need to know how it seems, or would glance.

As the psychologist of art Rudolf Arnheim famous, a draftsperson doing work from memory “may deny convincingly that he has nearly anything like an explicit image of [the object] in his mind”—yet, as he performs, “the correctness of what he is producing on paper” is judged and modified “according to some regular in the head.”

We have found that aphantasics keep these kinds of specifications. “MX,” the topic of the to start with scenario analyze of obtained aphantasia, could give specific descriptions of scenes and landmarks around his indigenous Edinburgh: “I can recall visual details,” he commented, “but I cannot see them.”

Aphantasia helps prevent the era of psychological illustrations or photos centered on knowledge of what factors look like, but it does not reduce that information serving as the foundation for an image manufactured with pencil and paper. Keane can attract a picture of Ariel for the reason that he is aware what individuals (and fish) look like, and that information—plus the skills acquired through study and practice—steers his hand accordingly.

Looking at vs. imagining

A different seemingly evident but vital point is that whereas psychological visualization can take place solely within the mind, drawing is a partly external act, taking position in front of the artist’s eyes. When you draw, you understand the marks you make. Every change, perceived, implies the following, in a suggestions loop. You really do not have to envision.

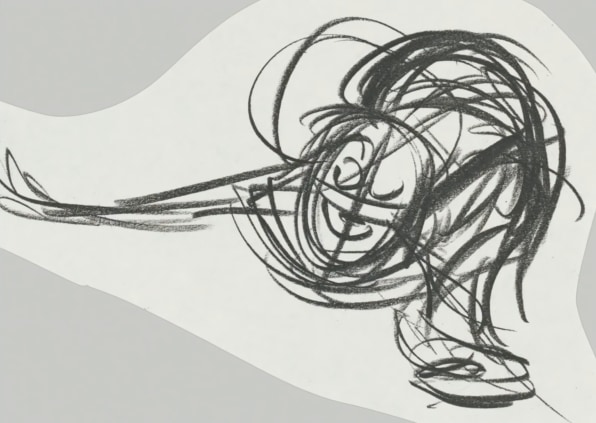

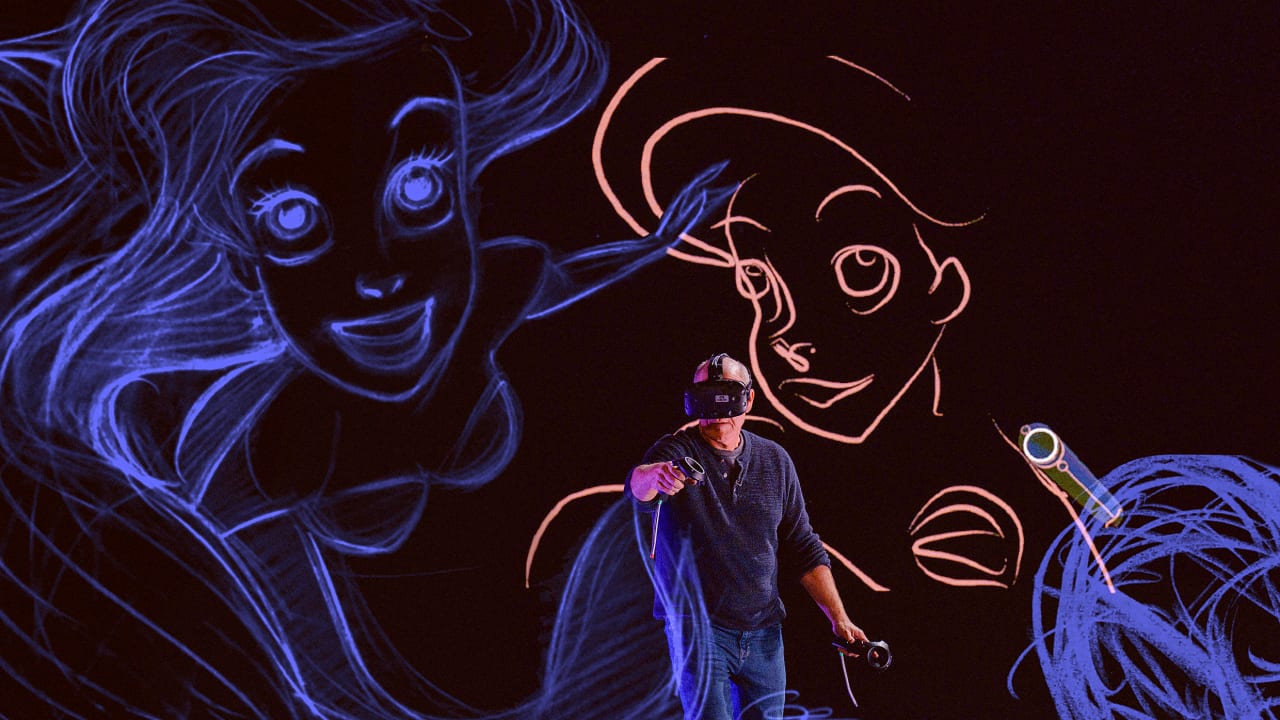

Numerous of the aphantasic artists we spoke to emphasized this facet of their innovative procedure: they would want to “get anything down” on the paper or canvas, or even begin with a preexisting graphic, which they can then change, erase or insert to. When Keane attracts Ariel, he starts with what he calls an “explosion of scribbles,” then highlights and subtracts traces right until he finds the variety that he would like.

Developing the Beast was a equivalent approach of demo and error. Keane started by copying the buffalo’s head that hung in his studio, then experimented with out characteristics from several other animals—a gorilla’s brow, a lion’s mane. A cow’s a bit drooping ears, he found, manufactured the Beast less threatening. The eureka minute was when he added human eyes. For Keane, it was “like recognizing any individual you know.” Somebody he understood, but could not photo.

Creative imagination diversified

The way that aphantasics like Keane function troubles the stereotype of the inventive artist that has held sway in excess of Western tradition for hundreds of years, at minimum because the Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari declared that “the greatest geniuses . . . are hunting for inventions in their minds, forming those fantastic strategies which their hands then convey.”

Vasari was referring to Leonardo da Vinci and his feedback show how we have come to think of inventive creativeness as currently being an inner potential, the fruits of which are simply reproduced in the outdoors world. The artist of genius is distinguished by the richness of their psychological conceptions as a great deal as their artworks.

But there are historical factors for the stereotype: profession-minded Renaissance artists seeking to define on their own towards the craftsman and his rule-subsequent, guide labor, for a single.

And while there are people who, encountering vivid imagery, do mentally preconceive their artworks, Keane and his fellow aphantasics display that the creative procedure can just as easily start with, and rely on, the materials globe all around them.

Matthew MacKisack is an affiliate research fellow at the University of Exeter. This posting is republished from The Conversation beneath a Creative Commons license. Study the authentic post.

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/604ad3acf728cc29468fec2e/0x0.jpg?cropX1=0&cropX2=846&cropY1=47&cropY2=523)

![See Inside the Amazing Homes of State Music’s Queens [Pics]](https://townsquare.media/site/204/files/2020/08/tim-mcgraw-faith-hill-mansion-california-pictures.jpg?w=1200&h=0&zc=1&s=0&a=t&q=89)